Succession to the Crown: Queen Anne

As the official public record since 1665, The Gazette has been recording successions to the Crown for over three centuries. As part of our ‘Succession to the Crown’ series, historian Russell Malloch looks through the archives at the accession and reign of Queen Anne, as described in The Gazette.

Chapters

Succession to the Crown paperback

To celebrate the new king’s coronation, The Gazette’s Succession to the Crown series is set to be published in paperback.

Available to pre-order now from the TSO Shop, the Succession to the Crown paperback explores the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy, and includes an exclusive chapter on the accession of King Charles III.

Due for release on 2 May 2023, find out more in the link below.

Accession Council

When King William III died in March 1702 the Crown and the royal authority passed to his sister-in-law, Princess Anne of Denmark, in accordance with the terms of the Act of Settlement of 1701.

Queen Anne came to the throne at a time of high tension in the nation’s relationship with both France and Spain, but the process of securing her succession was completed under less exceptional circumstances than in 1689, when the Westminster convention and the Edinburgh estates rather than any act of the English or Scottish parliament had determined that William and Mary should replace her father, King James.

King William died at Kensington Palace on the morning of 8 March, and his successor was proclaimed at the court at St James’s in line with recent practice, when a group of the lords spiritual and temporal met with the privy counsellors, the lord mayor of London and other “principal gentlemen of quality”. The accession proclamation was issued in similar terms to 1685, under which the Princess of Denmark was designated queen of England, Scotland, France and Ireland.

The Queen’s accession declaration committed her to preserve the religion, laws and liberties of the country and to secure the Protestant line. She also referred to the preparations that were being made to oppose “the great power of France”, a factor that would regularly influence the distribution of honours and the content of The London Gazette until the fall of Napoleon more than a century later.

The Gazette published the proclamation and the names of 33 individuals who signed the document that opened the last reign of the House of Stewart, and the last reign of a sovereign of the separate kingdoms of England and Scotland (Gazette issue 3790). The list was headed by Sir Nathan Wright, the lord keeper, who had served as one of the justices during William’s absence in 1701.

There were also reports from Ireland, where the lords justices, members of the Privy Council, the lord mayor of Dublin and “a great number of other gentlemen of quality” proclaimed the Queen’s accession on 18 March 1702 (Gazette issue 3796).

There was no equivalent meeting of the estates that preceded the joint offer of the Scottish crown to William and Mary, and The Gazette did not report any Accession Council being convened in Edinburgh, but it did publish the Queen’s letter to the Scottish Parliament in which she expressed her regret at not meeting in person owing to “the multiplicity of weighty and important affairs”, which included the European war, as well as work on a proposed union with England (Gazette issue 3819).

Queen Anne received the golden spurs during her coronation on 23 April 1702 as a symbol of her status as the fountain of honour (Gazette issue 3804), but she also followed precedent in granting royal favours in advance of the Westminster Abbey ritual. One of her first acts was to invest the Earl of Marlborough with the Garter, on the day before he was made captain-general “of all Her Majesty’s forces in England, or which are employed abroad in conjunction with the troops of Her Majesty’s allies”, and ambassador to the States General of the United Provinces (Gazette issue 3792).

Prince George of Denmark

The Act of Settlement did not provide for any part of the royal authority to be exercised by the Queen’s husband, Prince George of Denmark, and there was no repetition of a shared sovereignty of the kind that had existed under William and Mary.

There was therefore no lawful place for the Danish prince in using the royal powers, and he was not crowned as the Queen’s consort or given any formal role in the award of dignities, although he was familiar with aspects of the London-based honours system, as he was a duke in the English peerage and a knight of the Garter.

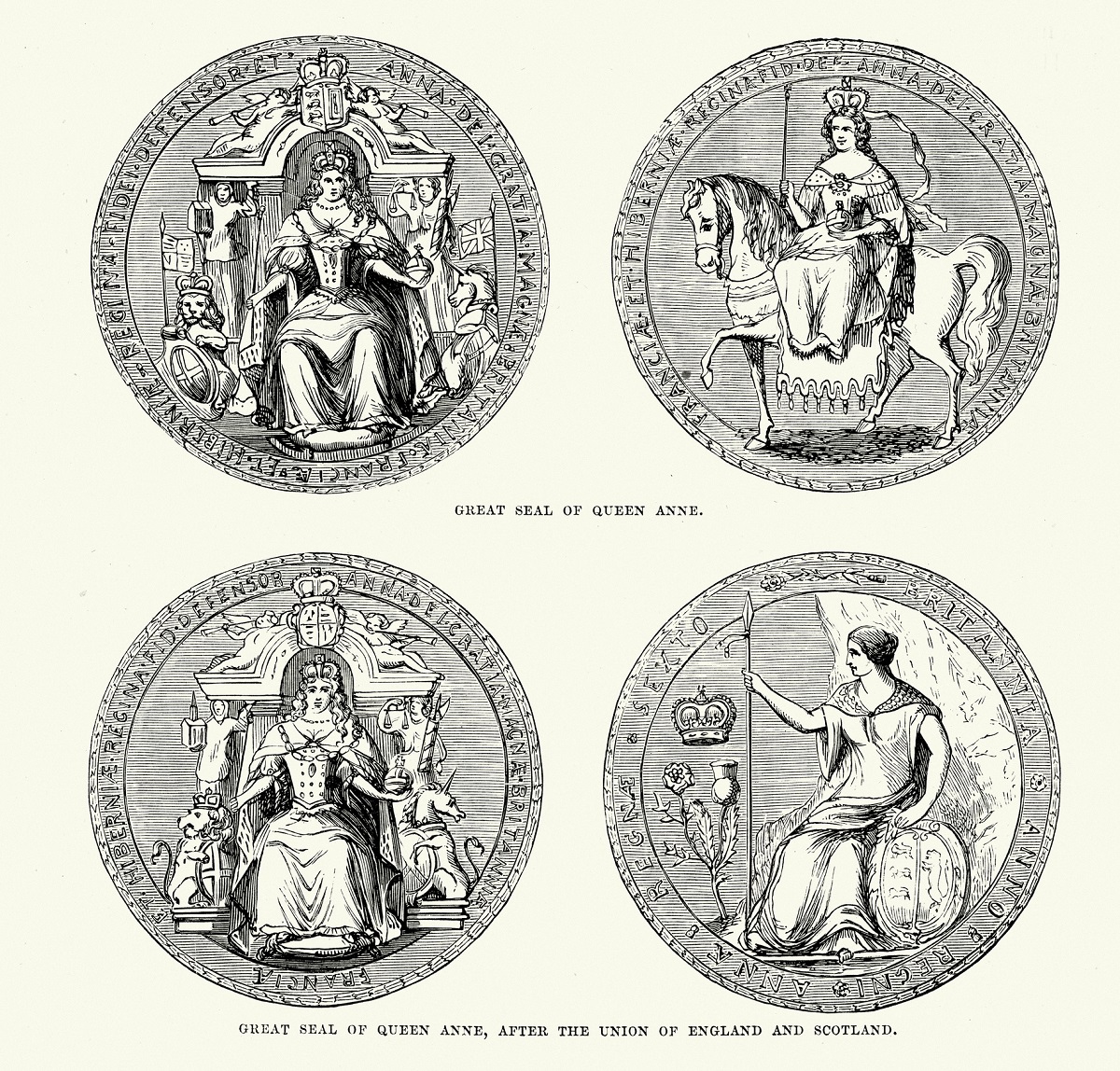

There was no reference to Prince George in the customary royal settings, such as in the great seal or coinage, which restricted the effigies and inscriptions to those of the Queen, but he received two prestigious offices after his wife came to the throne. The Gazette of May 1702 (Gazette issue 3812) announced that he had been made lord high admiral of England, and in June of the same year he became the constable of Dover and warden of the Cinque Ports (Gazette issue 3818).

Thistle revived

The only change to the supply of honours that arose between the start of the reign and the union of the kingdoms of England and Scotland was reported in February 1704, when The Gazette announced that the Order of the Thistle had been revived under the great seal of Scotland (Gazette issue 3992), and provided the names of the first in a series of knights which continues to this day, including the Earl of Seafield, who was one of the commissioners to negotiate the union of the kingdoms, and the Duke of Argyll, who played a prominent role in opposing the Jacobites.

The revival of the order also led to an early Gazette notice about the appointment of one of the officers who was responsible for administering aspects of the honours system on the sovereign’s behalf, as it reported that David Nairne had become the secretary of the Thistle and been knighted by the Queen (Gazette issue 3992).

The Crown of Great Britain

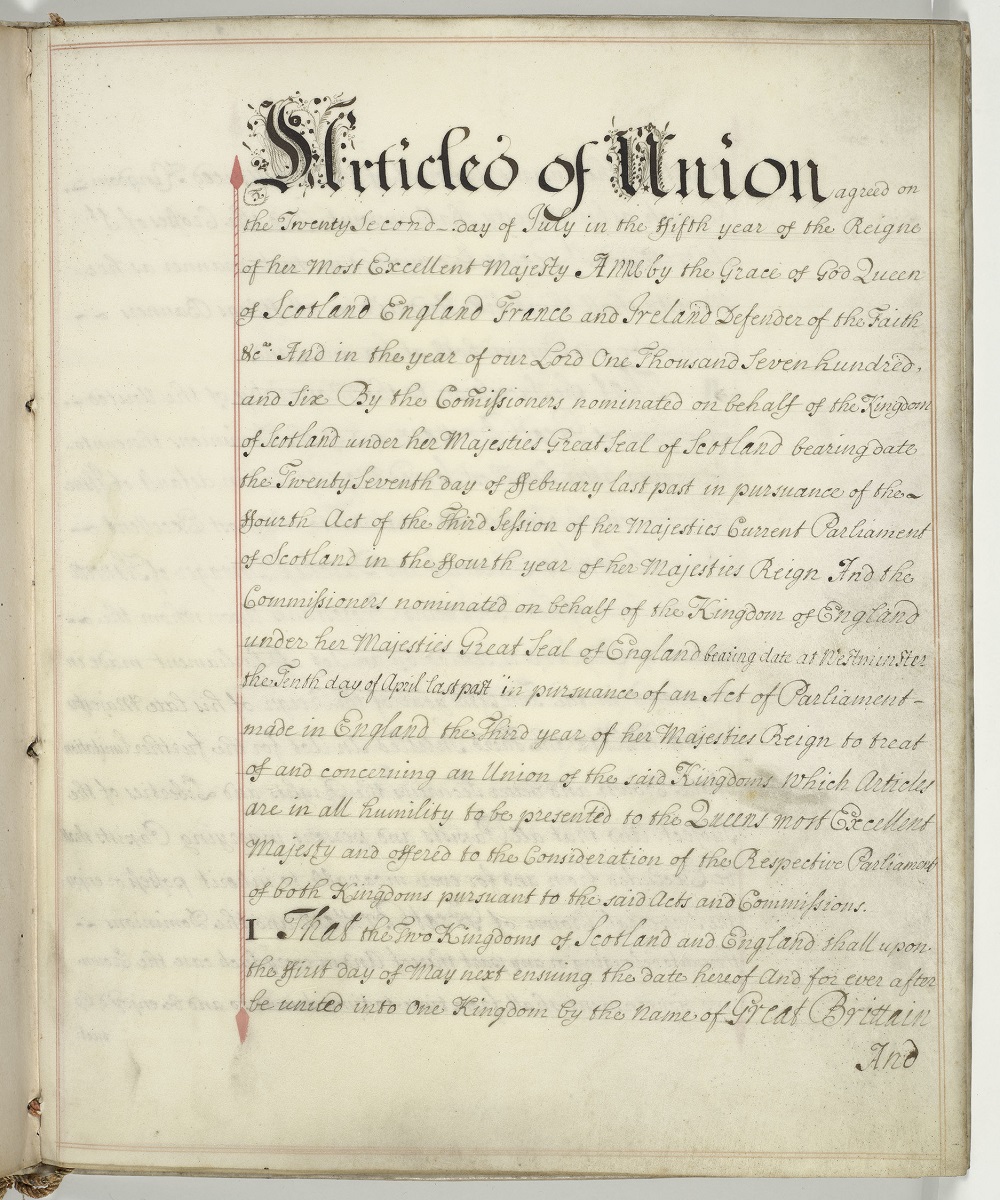

The nature of the royal authority was altered by the union of two of the kingdoms within the British Isles, which was the outcome of one of the earliest proposals to be brought before the Westminster Parliament during Queen Anne’s reign, and flowed from “an act for enabling Her Majesty to appoint commissioners to treat for an union between the kingdoms of England and Scotland” (Gazette issue 3807).

The Gazette charted some of the steps on the road towards the union, such as the nomination of the English commissioners in September 1702 (Gazette issue 3841), headed by Archbishop Tenison of Canterbury and Sir Nathan Wright, the lord keeper, whose signatures had headed the accession proclamation.

The negotiations took more than four years to complete, and The Gazette recorded the agreement to the terms of the union, and the ceremony at St James’s Palace in July 1706 when the Queen was presented with a copy of the articles by the lord keeper and the lord chancellor of Scotland in the name of the two sets of commissioners (Gazette issue 4247).

The Gazette also noticed other parts of the legislative process, including the Duke of Queensberry’s role as the high commissioner to the Scottish Parliament in touching the act ratifying the treaty of union with the royal sceptre at Edinburgh in January 1707 (Gazette issue 4299), while the Queen gave her assent to the English act “for an union of the two kingdoms” in March (Gazette issue 4312).

The Gazette did not refer to any special council or assembly of the great officers of state to approve or ratify the change to the Queen’s titles, but instead it published the royal proclamation which announced that a public thanksgiving for “the wonderful and happy conclusion of the treaty for the union” would be held on the day on which the kingdom of Great Britain was created (Gazette issue 4319), and reported that the Queen went in state to attend the service in St Paul’s Cathedral on that historic day, Thursday 1 May 1707 (Gazette issue 4328).

British dignities

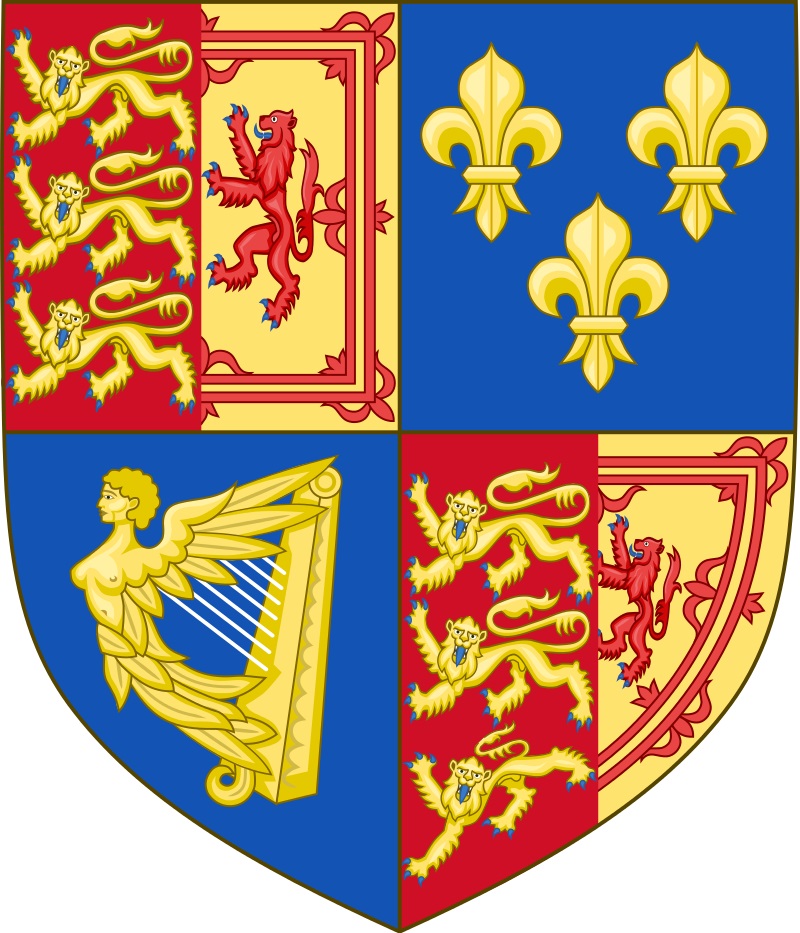

The honours system was affected by the union, as the grant of peerages and baronetcies under the separate great seals of England and Scotland came to an end, and instead any grants were as peers or baronets of Great Britain.

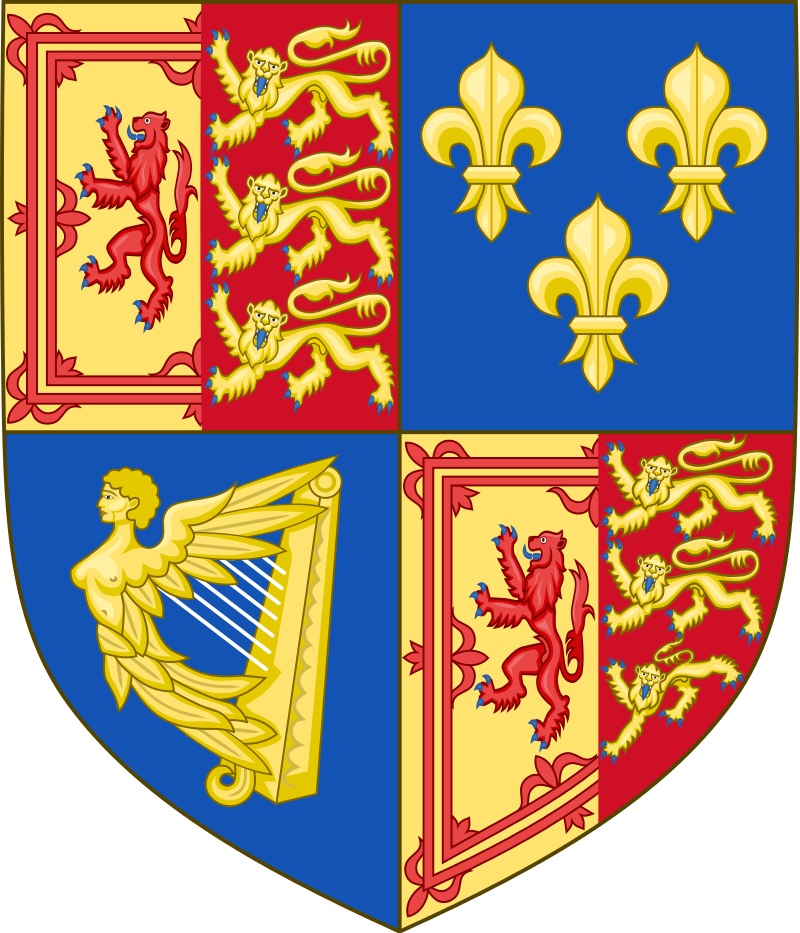

A great seal was prepared for patents and other purposes. It retained the effigy of the enthroned Queen placed between the English lion and Scottish unicorn, but now with a banner that combined the crosses of St George and St Andrew, while the reverse showed Britannia with a rose and thistle sprouting from a common stem. The first British seal also reflected changes to the royal arms, as the English and Scottish elements were now placed side by side in the first and fourth quarters of the shield, while the French fleur-de-lis and the Irish harp remained where they were.

Different rights were enjoyed by the pre-union peers, as the English noblemen continued to be entitled to sit and vote in the House of Lords, while the law obliged members of the old Scottish peerage to elect 16 of their number to act in a representative capacity for the term of each parliament. The Gazette routinely reported the proclamations for calling an election of the Scottish peers, either at the start of a new parliamentary session, or after the death of an existing peer. The first 16 were elected at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in June 1708 (Gazette issue 4447).

The provisions for electing the representative peers of Scotland remained in force until as late as 1963, while different rules applied in Ireland.

The Privy Council retained its role in the transfer of the royal authority after the union, and Accession Councils continued to be organised to manage the succession to the Crown after 1707. Membership of the council therefore remained an important element in the constitutional process.

The Gazette recorded the measures that were associated with the decision to end the separate English and Scottish councils and to create a Privy Council of Great Britain from 1 May 1708, the first anniversary of the union. Prince George of Denmark was admitted at Kensington Palace in May 1708, and several members of the old English council were sworn in at the same time (Gazette issue 4435).

Royal authority

The law relating to the succession to the Crown was altered to take account of the union, as the Queen’s ministers sought to maintain legislation that would extinguish the claims of the Stewarts, limit the influence of the King of France, and ensure that power passed to a Protestant.

The Gazette had previously reported the statute from March 1706 (Gazette issue 4211) that dealt with the pre-union situation in England, which required the Privy Council to cause the next Protestant successor to be proclaimed, and for the government to be administered by justices if, as seemed probable, Queen Anne’s successor was in Hanover when she died.

After the union, “an act for the security of Her Majesty’s person and government, and of the succession to the Crown of Great Britain in the Protestant line” received assent on 13 February 1708 (Gazette issue 4410). The statute – which is now rather confusingly known as the Succession to the Crown Act 1707 – made it treasonable to claim that “the pretended prince of Wales, who now stiles himself King of Great Britain, or King of England, by the name of James the Third, or King of Scotland, by the name of James the Eighth (or any other person) had any right or title to the Crown”.

The act regulated what was to happen when Queen Anne died and determined that the Privy Council “shall with all convenient speed cause the next Protestant successor entitled to the Crown of Great Britain ... to be openly and solemnly proclaimed in Great Britain and Ireland, in such manner and form as the preceding kings and queens respectively have been usually proclaimed after the demise of their respective predecessors.”

The severest penalty was imposed on any counsellor who did not comply, as the act declared that “all and every member and members of the said privy council, wilfully neglecting or refusing to cause such proclamation to be made, shall be guilty of high treason, and being thereof lawfully convicted, shall be adjudged traitors, and shall suffer pains of death”.

The post-union statute retained the English method for administering the government if the next Protestant successor should “be out of the realm of Great Britain in parts beyond the seas” and said that the holders of seven offices should be constituted the lords justices of Great Britain. The offices were those of:

- archbishop of Canterbury

- lord chancellor (or lord keeper of the great seal)

- lord high treasurer

- lord president of the council

- lord privy seal

- lord high admiral

- lord chief justice of the Queen’s Bench

They were permitted “to use, exercise, and execute all powers, authorities, matters, and acts of government, and administration of government, in as full and ample manner as such next successor could use or execute the same, if she or he were present in person”.

The statutory scheme allowed for the wishes of the Queen’s successor to be taken into account, as the heir to the throne could deposit three sealed instruments with the archbishop of Canterbury, the lord chancellor and their accredited resident in London, nominating “such and so many persons, being natural born subjects of this realm of Great Britain, as she or he shall think fit” to be justices in addition to the seven named office-holders.

The justices could not dissolve Parliament without express directions and could not assent to bills that repealed or altered certain statutes affecting the Crown, but no limit was placed on their ability to create peers or to award other honours, or to manage the business of the orders of knighthood. In practice, however, the justices never strayed into those areas of the royal authority.

Anne reigned for almost seven years as queen of Great Britain, and although she had more than a dozen children, none survived for more than a few years. She also had family links with several European houses but, in contrast to her predecessor’s regular visits to the Continent, she never travelled to Denmark to meet her husband’s relations, or to Holland where King William’s interests had passed to members of his Dutch family.

The reign therefore progressed without any delegation being required to manage the business of government or the award of honours because of the Queen’s absence from the realm.

Princess Sophia

The Gazettes of the early 18th century continued to be dominated by diplomatic, military and political news from Europe, and in June 1714 (Gazette issue 5232) the London editor noticed an event in a garden in Hanover that would impact on the government of the realm, as it concerned the welfare of the heir to the Crown, Princess Sophia, electress and duchess dowager of Hanover:

“In the evening she went out to walk in the gardens of Herrenhausen, where she was seized with a fit of apoplexy, and died in the arms of the Electoral Princess and the Countess of Pickenbourg, who were walking with her, before any other person could come up to her assistance.”

The princess would have become Queen Sophia had she survived for a few months longer, but died before her cousin Anne, and at a time when the Stewart claim to the British throne was being actively pursued by the Jacobites.

A few weeks after Sophia’s death the Privy Council acted on reports about unrest in Ireland that was linked to the Jacobite cause and issued a proclamation about the person “pretending to be, and taking upon himself the stile and title of King of England, by the name of James the Third.” The council required subjects “to use their utmost endeavours to apprehend the said Pretender wherever he shall land, or attempt to land, in Great Britain or Ireland, or any other of our dominions” so that he could be committed to goal for high treason, and all “for the safety of our person, and the security of the Protestant succession in the House of Hanover”.

A reward of £5,000 was offered for capturing the Pretender (Gazette issue 5236), but nothing was paid out before Queen Anne expired on 1 August 1714 (Gazette issue 5247).

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours.

Let us know what you think of this article by getting in touch. All feedback is welcome.

See also

Gazette Firsts: The history of The Gazette and royal coronations

Find out more

Succession to the Crown Act 1707 (Legislation)

Images (in order of appearance)

The Gazette

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Noonans of Mayfair

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Getty Images

Royal Arms of England 1707-14

Royal Arms of Scotland 1707-14

Lambeth Palace

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Publication date: 3 August 2022

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.