In debt and incarcerated: the tyranny of debtors' prisons

Extortion, brutal treatment and appalling conditions were experienced by imprisoned debtors. Andy Wood offers an overview.

Until 1861, only those who bought and sold goods to make a living could be made bankrupt. Others who were unable to pay their debts were referred to as ‘insolvent debtors’.

Debtors’ prison

Since the 14th century, debtors could end up in prison for non-payment of debts. Insolvent debtors who owed less than £100, and who were not traders, could be imprisoned indefinitely until the debt was repaid to creditors.

Prison could be avoided by declaring bankruptcy, but only if you were a merchant or trader. Even so, the costs were prohibitive: £10, which was equivalent to 10 to 20 per cent of the average annual income for the common worker in the mid-1800s.

In many cases, it was hoped that the debtors’ families and friends would repay the debt. Generally, conditions in prison depended on your standing in society. The warden of the prison would charge for accommodation – prisons were state-owned and subject to regulation, but were operated for private profit. If you could afford it, accommodation allowed access to a bar and shop, and even the pleasure of being allowed out during the day, with the potential to earn money to repay your indebtedness.

The concept of debtors' prison was of course flawed from the outset. If you were thrown into prison and had no family, you could not earn to repay your debts, which continued to accumulate. Most were left with little choice but to beg for alms from passers-by.

Conditions for debtors who could not raise money were appalling, with whole families cramped into overcrowded, cold, damp cells. Both women and men could find themselves imprisoned after falling into poverty.

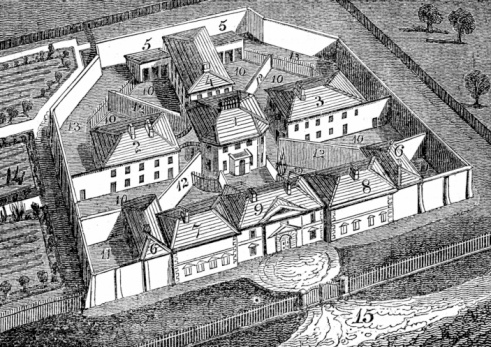

Prisons in London where debtors were held included Fleet (closed 1842); Faringdon (closed 1846); King's Bench (closed 1880); Whitecross Street (closed 1870); and Marshalsea (closed 1842).

Thomas Bambridge

Wardens were appointed by letters patent. Some wardens (such as Thomas Bambridge,

pictured, who become warden in 1728) were little short of sadistic, and deaths by

starvation, exacerbated by appalling conditions, were fairly common. In 1729, an act

gained Royal Assent prohibiting Bambridge from the office, after his cruelty had been

exposed by a parliamentary investigation, for his ‘unwarrantable and arbitrary power’:

Wardens were appointed by letters patent. Some wardens (such as Thomas Bambridge,

pictured, who become warden in 1728) were little short of sadistic, and deaths by

starvation, exacerbated by appalling conditions, were fairly common. In 1729, an act

gained Royal Assent prohibiting Bambridge from the office, after his cruelty had been

exposed by a parliamentary investigation, for his ‘unwarrantable and arbitrary power’:

‘An Act to impower His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, during the Life of Thomas Bambridge, Esq; to grant the Office of Warden of the Prison of the Fleet, to such Person or Persons as His Majesty shall think fit, and to incapacitate the said Thomas Bambridge to enjoy the said Office or any other whatsoever’ (Gazette issue 6778).

William Acton, warden of Marshalsea (Gazette issue 6787), was also put on trial by the Gaols Committee for his brutal treatment of prisoners, including the murder of Thomas Bliss, a carpenter, and James Thompson.

There are records showing some prisoners who managed to repay the debts for which they were imprisoned, but were detained because money was owed for food and lodging. There could even be fees charged for turning keys or taking irons off. When the infamous Fleet Prison closed, two debtors were found to have been there for 30 years.

Over half the population of England's prisons in the 18th and early 19th centuries were in jail because of debt, and during the same period, some 10,000 people were imprisoned for debt each year.

Imprisonment for debt only ended in 1869. The Debtors Act 1869 (Gazette issue 23524), with some exceptions, ceased the practice of indefinite imprisonment for non-payment of debt. In the same year, the Bankruptcy Act established the first statutory regime for preferential debts in bankruptcy, which included local and central taxes as well as wages and salaries of clerks, servants, labourers and workers.

The Gazette

Public notices regarding insolvent debtors and bankrupts, informing creditors about proceedings and applications for release, have appeared in The London Gazette for centuries, as a statutory requirement. Queen Anne’s Act to Relieve Insolvent Debtors in 1712 (Gazette issue 5014) stated that debtors could discharge a portion of their liabilities. One clause required the publication of insolvency notices in The Gazette.

Of the high profile individuals who were imprisoned for debt, perhaps the most notable was John Dickens, father of author, Charles Dickens. He was incarcerated in Marshalsea in February 1824, when Charles was just 12 years old.

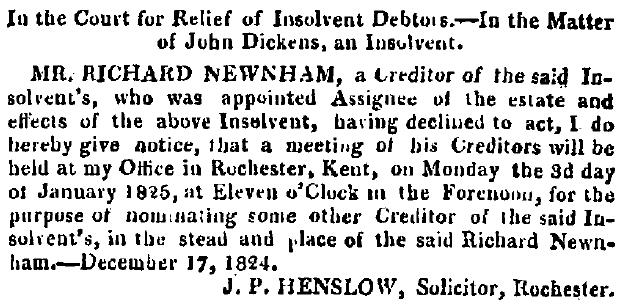

Reference is made to John in The London Gazette (issue 18092), when a meeting of creditors was announced. It is an entry from the Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors:

John owed a baker, James Kerr, £ 40 10s, and was committed to prison, where he lived with his family (apart from Charles, who worked in a blacking factory) until he was released three months later after receiving a family inheritance.

It clearly had a profound effect on Charles Dickens, who became a keen advocate for debtors’ prison reform. The whole issue of debt and social injustice is a recurrent theme in his work. Little Dorrit is a story about a debtor, imprisoned in Marshalsea over such a long-term that his three children grow up there. Dickens also wrote about Marshalsea in David Copperfield and The Pickwick Papers.

A happy ending…?

Fortunately, the treatment of debtors has evolved to be more equitable, though custodial sentences are still imposed in certain circumstances, for example, where a debtor has wilfully defrauded creditors of significant amounts.

Bankruptcy and debt relief orders are a means of addressing personal insolvency, giving the debtor the opportunity of a fresh start, while creditors are afforded some protection, as bankruptcy proceedings are placed in the public domain by publication in The Gazette.

About the author

Andy Wood is associate director at Wilson Field. Former R3 Yorkshire and Humberside regional chairman and committee member, Andy is a licensed insolvency practitioner.

See also: The historical treatment and perception of bankrupts

Sources:

Ashton, J, ‘The Fleet: Its River, Prison, and Marriages’, Nabu Press, 2010

Stubley, P, ‘A Pauper's History of England: 1000 Years of Peasants, Beggars and Guttersnipes’, Pen and Sword Books, 2014

The National Archives, ‘How to look for records of...Bankrupts and insolvent debtors’ [online]

White, J, ‘Pain and Degradation in Georgian London: Life in the Marshalsea Prison’, Oxford Journals, Arts & Humanities, History Workshop Journal, Volume 68, Issue 1, pp. 69-98 (online, accessed 09/12/2016)