War on two wheels: British army cyclists 1914-1918

The British army of the late-19th and early-20th centuries proved to be quick at adopting emerging equipment and technologies, particularly when it came to battlefield mobility.

Despite remaining heavily reliant on the horse for transport and  haulage, the army entered World War 1 as the most mechanised in the world, and maintained

that position throughout the conflict. It proved to be an important factor in the

army’s victories of 1918 and the logistical support of the ‘all arms’ methods that

achieved them.

haulage, the army entered World War 1 as the most mechanised in the world, and maintained

that position throughout the conflict. It proved to be an important factor in the

army’s victories of 1918 and the logistical support of the ‘all arms’ methods that

achieved them.

In our modern era of aircraft, helicopters, trucks and armoured vehicles, it is easy to forget that the humble bicycle was part of this mechanisation.

The bicycle's role in warfare

As early as the 1880s, the army began to include the bicycle in its armoury. Prior to this, the army relied on men or horse transport to cover the ground. Each had limits on speed and range, and the horse needed much by way of logistical support for its feeding and care.

With a bicycle, an armed man could move relatively quickly across even poor ground and with longer range than his marching capability. In other words, the bike brought new possibilities for the army to project its forces to where they were needed.

Formation of bicycle units

Although bicycle troops had been used during the Second Boer War, the first large-scale formalisation of their role came with the Haldane army reforms of 1908 (Gazette issue 28127) and the creation of ten bicycle units for the Territorial Force. Of these, most were established as units of infantry regiments (an example being the 7th (Cyclist) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment), while others were independent cyclist units, such as the Northern Cyclist Battalion.

Early in the war, a cyclist company was added to each British division. So for example, the structure of the 1st Division included the 1st Divisional Cyclist Company. These units were technically of the regular army. All of the ‘new army’ divisions raised under Lord Kitchener’s instructions in 1914 also included a cyclist company. Soldiers were seconded to these units from other regiments.

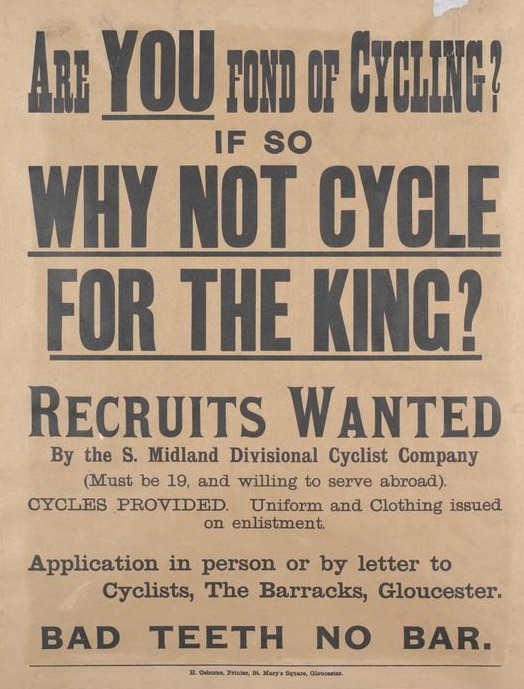

Recruitment efforts in 1914-1915 aimed at attracting men who were already cyclists, or who were at least interested in things mechanical. One fascinating poster, trying to enlist men for the 48th (South Midland) Divisional Cyclist Company in the Gloucester area, said, ‘Are you fond of cycling? Why not cycle for the King?’, and went on to add, ‘Bad teeth no bar’!

The primary roles of the cyclists were in reconnaissance and communications (message taking). They were armed as infantry and could provide mobile firepower, if required. Those units that went overseas during WW1 continued in these roles, but also carried out trench-holding duties and manual work, once the mobile phase of war had settled down into entrenched warfare. They also began to be used for patrol work in the rear areas behind the front lines and in traffic control duties.

Pte William Liddell DCM

Work in the trenches put the cyclists in the most acute danger, and in these circumstances, they carried out many acts of great bravery. An example is that of 3149 Pte William Liddell of the 9th Divisional Cyclist Company, a 33-year-old married man who came from Leith in Scotland, and who had previously been with the Seaforth Highlanders. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (junior only to the Victoria Cross). The London Gazette published the citation for this award (Gazette supplement 2692):

'Hearing a wounded man of another battalion, who was lying out in the open, calling for assistance, he, accompanied by Captain Campbell, jumped over the parapet and together they carried the wounded man to safety. Private Liddell’s clothing was hit in several places by enemy bullets.'

His action was during the Battle of Loos in September 1915 (despatch, Gazette supplement 29347), at Madagascar Trench near Auchy-les-Mines. Sadly, he would later die of wounds near Ypres on 25 February 1916.

Army Order 477

The formation of a specialist army cyclist corps was authorised by Army Order 477, dated 7 November 1914. When the order came into effect, all men who were serving with the divisional cyclist companies, or who were in training as cyclists to provide drafts for those companies, would be transferred into the new corps.

The men were given the new cap badge of the corps and were also renumbered in a new corps sequence. The order did not affect the territorial cyclist units or the men serving in them, as they kept their own regimental identities. Men being enlisted for the duration of the war could now be appointed directly to the new corps. The pay of the cyclists was to be the same as that of the infantry. Additional ‘proficiency pay’ would be given to men who qualified as a proficient cyclist and who had the necessary physical endurance.

In May and June 1916 the divisional cyclist companies were withdrawn from the divisions to form a cyclist battalion for each corps headquarters (so, for example, the IX Corps Divisional Cyclist Battalion came into existence and was a unit of the Army Cyclist Corps). The army retained this structure for the rest of the war.

It's not easy to determine how many men served in the various cyclist units. Some 20,000 names can be traced from the campaign medal rolls, but this does not include the many who served in cyclist units at home. The records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission list 862 men of the Army Cyclist Corps who lost their lives in WW1; they lie or are commemorated in every theatre of war in which the British army was present. There is no regimental memorial to these men, although there is a memorial to cyclists who took part in the war in Meriden, near the great bicycle manufacturing centre of Coventry.

About the author

Chris Baker is a professional military historian. A former chairman of the Western Front Association, he has an MA in British Military History and is creator of The Long, Long Trail.

Image: Are You Fond of Cycling?, © IWM