Conscription in World War 1

Professor Ian Beckett explains how the British government went about boosting army numbers in WW1 through

legislation – and how localism at times mitigated national policy directives.

Professor Ian Beckett explains how the British government went about boosting army numbers in WW1 through

legislation – and how localism at times mitigated national policy directives.

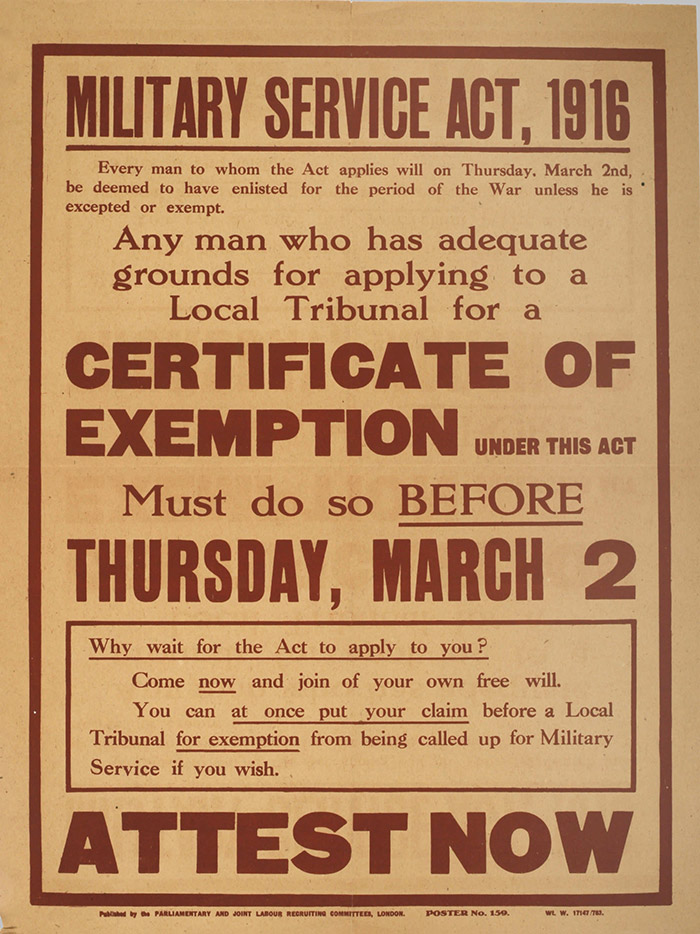

Faced with appalling casualty figures and a decline in voluntary recruiting, the British government introduced the first Military Service Act in January 1916 (Gazette issue 29454), rendering all single men and childless widowers between the ages of 18 and 41 liable to conscription.

The Military Service (No 2) Act then extended conscription to all men between these ages in June 1916, the age range being subsequently extended to 50 in April 1918 (Gazette issue 30646). Provision for the conscription of men up to the age of 56 (and the extension of conscription to Ireland for the first time) if the need arose was also incorporated into the 1918 legislation, but never implemented. In addition, there was legislation in July 1917 to enable the conscription of French and Russian citizens residing in Britain.

Conscription was an unprecedented intrusion by the state into the lives of individual British citizens, for though often debated, compulsion had not been applied to the regular army since short-lived legislation in the early 18th century that had affected only debtors, vagrants and other marginal elements within society.

The militia, raised entirely for home defence, had been subject to compulsion on occasions between 1757 and 1831, but the militia ballot had been deeply unpopular and the public had shown no support for conscription. Indeed, it was the voluntary system of enlistment that most differentiated the British army from those of the great continental powers.

The need to implement compulsion, therefore, represented one of the most significant indications of the impact of ‘total war’ upon the British state, its institutions and its communities between 1914 and 1918. It was not implemented without an agonised debate that grew in intensity, the last throw of the voluntary system being the failure of the so-called Derby Scheme between October and December 1915, by which men were encouraged to attest their willingness to serve if called upon to do so.

Those conscripted could appeal to local military service tribunals for exemption from military service on the grounds of conscience, family circumstances, or by reason of employment in key occupations.

The tribunals (Gazette issue 29489 and 29492) could either insist that the individual concerned enlist, defer entry, or they could exempt him. Composed mostly of local representatives of the ‘great and good’, though also including women, employers and representatives of organised labour, the tribunals have had a bad press. It has been suggested that tribunal members were unduly influenced by the military representatives of the War Office and especially hostile to exemption claimed on the grounds of conscience.

In reality, only 16,500 claims for exemption were made on the grounds of conscience between 1916 and 1918 when compared, for example, to over a million exemptions granted on medical grounds in the last 12 months of the war alone. The efficiency and reliability of medical boards was questioned, but the totals exempted are suggestive of the levels of physical deprivation in pre-war, urban Britain. Moreover, there were still 2.5 million men in reserved occupations by 1918, despite the progressive withdrawal of many occupational exemptions.

Through an (erroneous) assumption of a lack of surviving documentation, the process of conscription has not been subject to detailed investigation until relatively recently. Much earlier work was based upon contemporary press reports that tended to highlight the unusual rather than the routine. In fact, extensive records have survived for Cardiganshire Middlesex, Northamptonshire, Peeblesshire and parts of Warwickshire. Many county and other local archive depositories also have surviving documentation of one kind or another.

What is now apparent is how far localism mitigated national policy directives. Tribunals varied enormously in attitudes but, rooted as they were within the local community, all were mindful of local needs in terms of the economic vitality of agriculture, industry and trade. The War Office was especially suspicious of the numbers exempted on condition that they served in the domestic volunteer force, the Great War equivalent of the Home Guard of World War 2. Decisions might also be gendered in terms of those occupations that tribunals believed should only be undertaken by men.

Some 4.9 million men were enlisted in the British army between 1914 and 1918, of whom 2.4 million enlisted prior to the introduction of conscription and 2.5 million after it. It is calculated that only 1.3 million men were actually conscripted. Government manpower policy was far from properly established until late 1917, but in any case, the experience of conscription raises significant questions as to how far Britain became a much more centralised state during and after WW1, or if the local government norms of the Edwardian period persisted into the 1920s and beyond.

Lessons were learned, however, and Britain entered World War 2 with coherent manpower policies, and there was an appropriate schedule of reserved occupations ahead of the re-introduction of conscription in April 1939 (Gazette issue 34630).

About the author

Professor Ian Beckett retired as professor of military history from the University of Kent in 2015 but remains an honorary professor there. His research focuses on British auxiliary forces, World War 1, and the late Victorian army. He was chairman of the council of the Army Records Society from 2000 to 2014, and is secretary to the Buckinghamshire Military Museum Trust.