This month in history: Great Fire of London

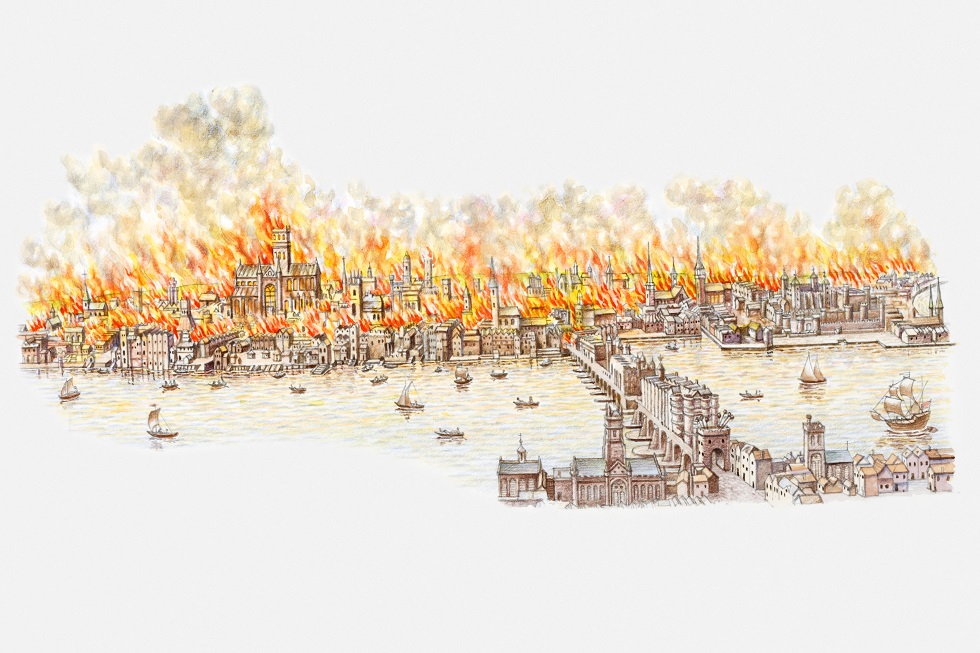

Shortly after midnight on Sunday 2 September 1666, a blazing fire broke out at a bakery on Pudding Lane, London. As part of our ‘this month in history’ series, we look at the Great Fire of London, as described in The Gazette.

How did the Great Fire of London start?

The Great Fire of London started shortly after midnight on Sunday 2 September 1666 when a blazing fire broke out at the bakery of Thomas Farriner on Pudding Lane after he failed to properly extinguish his oven.

Fires were common in the 1600s but they were also usually quickly put to an end. However, in the summer of 1666, it had been hotter than usual and there hadn't been any rain for weeks. As a result, the wooden houses and buildings in London were tinder dry. The fire therefore spread rapidly west across the City of London, jumping from house to house thanks to strong winds.

Rumour and fear quickly griped the capital with many believing that the fire was an act of terrorism caused by the on-going Second Anglo-Dutch War. The resulting disruption to news and communications only heightened fears, with the General Letter Office, which most of the country’s post passed through, burning down early on Monday morning.

However, The London Gazette managed to publish its Monday issue (Gazette issue 84), highlighting the fire, before the printer's premises at Baynard’s Castle went up in flames. A week later, The Gazette described accurately how the fire started and spread, having been printed at the Savoy (Gazette issue 85): ‘It hath been thought fit to satisfying the minds of to many of His Majesties Subjects, who must needs be concerned for the Issue of so great an accident, to give this short, but true Account of it.’

How did the Great Fire of London spread?

Pulling down houses in the path of fires was an often-used way of containing outbreaks in the 1600s. Houses were demolished with firehooks (hooked poles) or explosives in order to create a ‘firebreak’, ie containing the fire by not giving it anything to spread to. However, once he arrived at the scene on Pudding Lane, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, refused to allow demolition of the adjoining houses to take place because he didn’t want to upset the tenants, remarking: "Pish! A woman could piss it out". According to The Gazette, this indecision led to the spread of the fire: ‘care was not taken for the timely preventing the further diffusion of it by pulling down houses, as ought to have been’.

By Sunday afternoon, the fire had spread quickly due to high winds. King Charles II ordered houses west of the fire to be pulled down but the fire was already out of control, spreading quicker than houses were being pulled down.

By Monday 3 September, half of London was in flames, with the fire expanding north

and west. According to The Gazette, the fire ‘was raging in a bright Flame all of

Monday and Tuesday’. In 1666, London Bridge was the only physical connection between

the City and the south side of the Thames - it was also itself covered with houses.

As well as fears for those living on the bridge (Samuel Pepys recorded concern for

friends living on the bridge in his diary), there were also fears that the flames

would cross the bridge and reach Southwark. However, the open space  between buildings on the bridge acted as a firebreak and the fire never significantly

reached the south bank.

between buildings on the bridge acted as a firebreak and the fire never significantly

reached the south bank.

On Tuesday 4 September, the fire leaped the River Fleet and destroyed St Paul's Cathedral. Luckily the Tower of London had escaped the inferno and the Tower’s garrison used gunpowder to blow up houses that lay in the path of the fire, creating effective firebreaks to halt further spread. ‘By the favour of God the Wind flackned a little’ on Tuesday night, according to The Gazette, and on Wednesday 5 September the fire was brought under control.

By Thursday the Great Fire of London ‘was wholy beat down and extinguished’.

How many people died during the Great Fire of London?

Though the Great Fire of London destroyed 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, St Paul's Cathedral, and most of the buildings of the City authorities, incredibly only six people verifiably died in the fire. The baker who started the fire, Thomas Farriner, managed to escape the bakery out of an upstairs window along with his family and a servant. However, a bakery assistant did die in the flames. While the death toll was relatively small, it’s estimated that the homes of 70,000 of the city's 80,000 inhabitants were destroyed.

Following the Great Fire, fears of foreign arsonists and of a French and Dutch invasion were rife in London. So much so, a mentally unstable French watchmaker called Robert Hubert confessed to starting the fire deliberately and was quickly hanged at Tyburn on 28 September 1666. After his death it was discovered that Hubert could not have started the fire, as he’d been on board a ship in the North Sea and had not arrived in London until two days after it started.

A Monument to the Great Fire of London was constructed on Pudding Lane between 1671 and 1677 and can still be seen today. It was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, who was also given the task of rebuilding much of London. Wren rebuilt 52 of the City churches and designed the new St Paul’s Cathedral, which began construction in 1675 and was completed in 1711. In memory of Wren there’s an inscription in the Cathedral set in a great circle in the floor directly under the dome which reads: ‘Si monumentum requiris circumspice’. Translated, it means: ‘If you seek his monument, look round’.

See also

The Gazette and its role during events of national significance

This month in history: The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

Image: Getty Images

Publication date: 1 September 2020

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.