Succession to the Crown: King Edward VII

As the official public record since 1665, The Gazette has been recording successions to the Crown for over three centuries. As part of our ‘Succession to the Crown’ series, historian Russell Malloch looks through the archives at the accession and reign of King Edward VII, as described in The Gazette.

Chapters

Succession to the Crown paperback

To celebrate the new king’s coronation, The Gazette’s Succession to the Crown series has been released in paperback.

Available to order now from the TSO Shop, the Succession to the Crown paperback explores the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy, and includes an exclusive chapter on the accession of King Charles III.

Find out more in the link below.

Accession Council

Four Accession Councils were organised during the 20th century; a century that saw some familiar precedents being followed to manage the succession to the Crown, as well as significant additions being made to the honours that could be awarded in the name of the sovereign.

The century also saw a modified approach being taken to delegate the royal functions when the sovereign left the United Kingdom, or was otherwise unable to perform his or her duties.

The first of the four councils took place after Queen Victoria died on the Isle of Wight, and this would be the last time the sovereign’s eldest child did not succeed to the Crown because of their gender, as the Dowager German Empress was passed over in favour of her younger brother, the Prince of Wales.

The London Gazette reported the meeting of the counsellors and public figures at St James’s Palace on 23 January 1901, the day after the Queen’s death (Gazette issue 27270). Most of the earlier Accession Councils had taken place on the day the sovereign expired, rather than one or more days later. Even so, King Edward VII’s reign was always deemed to begin on 22 rather than 23 January 1901, and the earlier date was used in 1910, 1952 and 2022 when the dates of the death and Accession Council also differed.

The proclamation explained that Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, had become king of the United Kingdom and emperor of India, and omitted any reference to the more important nations of the British Empire where he exercised regal power, as in the case of Australia, Canada and New Zealand that had all been added to the royal domain since The Gazette first reported the work of an Accession Council.

The document carried the signature “F. Cantaur” for Frederick Temple, the archbishop of Canterbury who would later crown the King. Many of Temple’s predecessor had also subscribed the proclamation and crowned the sovereign, as happened when William Howley attended the council and later placed the crown on the heads of King William IV in 1830-31 and Queen Victoria in 1837-38.

The names that appeared beside Archbishop Temple recalled the political power that determined the true extent of the royal authority, as the document bore the signatures of past, present and future prime ministers – Lords Rosebery and Salisbury, together with Herbert Asquith, Arthur Balfour and Henry Campbell-Bannerman.

King Edward

The Prince of Wales decided to take the title of Edward the Seventh rather than Albert the First, and The Gazette reported the accession declaration in which he explained that he had “resolved to be known by the name of Edward, which has been done by six of my ancestors. In doing so I do not undervalue the name of Albert, which I inherit from my ever to be lamented, great and wise father, who by universal consent is I think deservedly known by the name of Albert the Good, and I desire that his name should stand alone.”

The reign did not require any bill to deal with a regency during a minority, as all of the King’s children were over the age of 18 years when he came to the throne, but a number of legislative changes were made that impacted on the form rather than the substance of the royal authority.

On 17 August 1901 assent was given to the Royal Titles Act which enabled the King to make an addition to his titles in recognition of the dominions. This measure reflected the outcome of a colonial conference in the 1880s, which had expressed a desire that some change might be made to indicate the vast growth in the colonial dominions that had taken place since the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign (Gazette issue 27347).

The bill passed through Parliament amid much division along religious lines that recalled the conflict of the Stewart era, but a proclamation was eventually issued on 4 November 1901 that reflected the altered state of the royal domain, and The Gazette reported that Edward was now “king of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of the British dominions beyond the seas”, as well as continuing to be emperor of India (Gazette issue 27371). The amended title was first used at an Accession Council in May 1910 when King George V came to the throne.

Legislation was also put in place that affected members of the Privy Council and other public officials, as the Demise of the Crown Act from July 1901 (Gazette issue 27330) provided that as from the death of Queen Victoria “the holding of any office under the Crown, whether within or without His Majesty’s dominions, shall not be affected, nor shall any fresh appointment thereto be rendered necessary, by the demise of the Crown.”

Foreign travel

The King went “beyond the seas” on several occasions, but no guardians or justices were appointed to exercise the royal authority when he did so, which followed the policy for managing state business that applied during his mother’s trips to Europe that began with her visit to France in 1843.

Edward’s earliest journeys were for family business, as he left London on 23 February 1901 to visit his sister, the Dowager German Empress, and was attended by no more than his doctor and equerry, Captain Frederick Ponsonby, who had helped to organise Queen Victoria’s funeral and would support the royal authority on many occasions before his death in 1935.

The Gazette reported no patent to cover the King’s first absence, or when he left again to attend his sister’s funeral at Potsdam in August. The King also visited Denmark and performed his royal functions while he was in Europe, as when he invested his envoy at Copenhagen with the insignia of the Order of St Michael and St George. Edward did not return to England until 25 September 1901 and yet, once again, no patent was issued to deal with the affairs of state while the King met his relations, and instead he undertook to return if it was necessary to hold a Privy Council.

Measures were later put in place to delegate the authority to hold councils, but the text of the King’s commission was never gazetted. In 1906 the lord chancellor, prime minister and lord president were given that authority, and the clerk of the Privy Council recorded that the nearest precedent to the meeting of the commissioners in council on 4 April 1906 was when the justices met during King George II’s last visit to Hanover in the mid-18th century:

“Lord Ripon [lord privy seal] expressed a fear that I might be involving him in proceedings for which he could be asked to pay the penalty of his head on Tower Hill, but I assured him that every step had been taken upon the responsibility and with the approval of the highest legal authority. Certainly no one could be more scrupulous than the Lord Chancellor in subscribing to the most exacting requirements.” (Fitzroy, 1928)1

The Gazette reported some of the orders Lord Ripon and his colleagues made, which included a preamble about allowing the commissioners “in His Majesty’s absence from his realm in foreign parts” to hold his Privy Council and “to signify thereat his approval of any matter or thing whereunto they should be so authorized by writing under His Majesty’s sign manual” (Gazette issue 27904).

The King often spent the months of March and April in Biarritz in the south of France, and similar commissions relating to the Privy Council were issued in 1907 and 1908, but this time the authority was delegated to the Prince of Wales rather than the prime minister and members of his administration.

The sovereign’s trips proved to be controversial, particularly so in 1908 when Herbert Asquith had to travel to Biarritz to succeed Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman as prime minister. The King returned to Buckingham Palace on 16 April and held a council on the same day, when Asquith was sworn as first lord of the Treasury (Gazette issue 28129), and seals were delivered to members of his government, including the colonial secretary, the Earl of Crewe, who would play a central role in matters affecting the Crown over the next few years.

Asquith’s reception in Biarritz led to an official statement being issued in 1909 – just before Edward embarked on what many regarded as another holiday – which explained that the French trips were “entirely on account of his health, his doctors having strongly urged him to absent himself from this country during the months of March and April.”

The Gazette recorded the issue of further commissions to manage official business in 1909 and 1910, and some of the council’s orders that were issued while the King was away, the last of which were made just days before he returned from France for the last time on 27 April 1910 (Gazette issue 28361).

Foreign awards

The extent of the King’s travels is revealed by the nominations to the Victorian Order that appeared in The Gazette for services rendered during his many visits, starting in the spring of 1903 with his reception in several European capitals, including Lisbon (Gazette issue 27560), Paris and Rome, and ending in 1909 with his state visit to Berlin and his less formal activities in Biarritz.

The royal authority continued to be delegated in some of the orders for reasons that were not connected with the King’s travels, as several governors and governors-general were authorised to hold investitures, which became a more important aspect of their public duties as the number of colonial awards increased.

The King also continued to issue commissions to deliver the Garter to foreign sovereigns, as happened in May 1902 when the Duke of Connaught invested the King of Spain in Madrid, and in February 1903 when Viscount Downe presented the ensigns to the Shah of Persia in Tehran. The Garter missions and colonial ceremonies were always exceptions to the general rule, as the King performed many investitures in person, with an event being organised at Buckingham Palace in July each year to deal with the summer honours list, followed by a second investiture in December for those who were named in the birthday list in November.

Altered images

The accession of King Edward VII followed the first demise of the Crown that led to any material changes being made to the royal emblems that appeared on the insignia of certain orders, decorations and medals that were conferred by the sovereign.

With the exceptions of the Guelphic Order, and the less formally constituted Royal Family Order of the House of Hanover, the effigy and/or cypher of the reigning sovereign did not feature in the insignia that was worn by members of any order until 1861, when Queen Victoria’s portrait was adopted by the Order of the Star of India.

Victoria’s effigy and cypher were introduced in many more settings as the reign progressed, and so the question was what to do after she died. The response was mixed, with the Queen’s portrait being retained for the Star of India and Indian Empire, and her cypher remaining in the Crown of India and Victorian Order, while the combined V.A. cypher for Victoria and Albert stayed on the Albert Medal. On the other hand, King Edward’s effigy and cypher replaced his mother’s emblems on the Royal Red Cross and Royal Victorian Medal, while E.R.I. displaced V.R.I. on the badge of the Distinguished Service Order and the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal.

The warrants of appointment connected with the award of honours were now issued in far greater numbers than when Victoria came to the throne in 1837, and so it was a much larger job to alter the text to show Edward’s style and titles. A similar situation arose in other areas of public business, as the authorities had to determine what changes, if any, should be made to the royal emblems. There was ample precedent for changing the effigy on the coinage of the realm, but no precedent to guide what to do with the postage stamps, which had only carried the Queen’s effigy since 1840.

Precedent was certainly followed in the matter of the great seal, and so Edward’s seal was commissioned and brought into use in 1904. The design contained several references to the British dominions beyond the seas, as the seal showed Edward sitting between figures representing commerce and justice, with St Michael and St George above. The counter seal portrayed him on horseback, and in the background an ironclad and a sailing vessel, symbols of the royal and commercial navies, and below a scroll inscribed “Canada, West Indies, Newfoundland, British Africa, Gibraltar, Malta, India, Eastern Colonies, Australia, New Zealand”.

Coronation honours

The Gazette demonstrated the extent to which the number of honours increased during the reign, as Edward used his royal authority to create rewards that could be distributed by the prime minister, as well as honours that fell within his personal control, in line with the system that had been operating within the Victorian Order since 1896.

The expansion began during the first year, as the King was present at Marlborough House on 15 June 1901 when the Privy Council approved an Admiralty proposal to institute the Conspicuous Service Cross to reward “meritorious or distinguished services before the enemy” that were performed by lower ranking officers of the Royal Navy.

Announcements about more important additions to the British honours system were planned to coincide with the coronation, which was due to take place on 26 June 1902, but was postponed until 9 August because of the King’s health. A few days before the original date a patent was issued under the great seal to create the Order of Merit to reward exceptionally meritorious service in the navy and army or towards the advancement of art, literature and science. The founder members included Lords Kitchener and Roberts, who had commanded the recent military operations in South Africa, and renowned scientists Lords Kelvin and Lister (Gazette issue 27470).

The coronation honours reflected the international range of the King’s domain, as knighthoods were conferred on a judge of the Supreme Court of Canada, the chief justice of Western Australia, and the mayor of Auckland in New Zealand. The King also signed warrants for colonial nominations to the orders, among them awards for the prime ministers of Australia and the Cape of Good Hope.

The next coronation addition was created by warrant on 8 August 1902, when the Imperial Service Order and its medal were introduced to reward the work of members of the administrative or clerical branches of the civil service (Gazette issue 27463). The Crown’s overseas reach was demonstrated by the initial structure of the order, which had up to 425 members, of which 75 places were dedicated “to the civil services of our colonies and protectorates”. The first overseas award was granted to the deputy minister of finance of Canada (Gazette issue 27559).

The third coronation addition was known as the Royal Victorian Chain and was a mark of the sovereign’s special esteem that was mainly confined to members of the royal family but was also given to Archbishop Temple of Canterbury after the coronation. The decoration was regularly worn by the King and his immediate successors, but largely disappeared from public view following the death of King George VI.

The formal connection between the Crown and the new honours was made in the usual manner, as the founding documents stated that King Edward and his successors were to be the sovereigns of the Order of Merit and the Imperial Service Order, while the insignia of the members of both orders contained the usual emblems of the royal authority, the crown and cypher.

Coronation medals

The 1902 coronation followed the traditional service, with the golden spurs being used for the first time since 1838 to symbolise the King’s investiture with his royal authority, but a new element was introduced to the ceremonial to reflect the higher profile the honours system now enjoyed across the Empire, as several officers of the orders of knighthood were allocated places in the procession (Gazette issue 27489).

The crowning of King Edward and Queen Alexandra was commemorated by the issue of medals that were designed to be worn and so, for the first time since 1685, The Gazette did not report the treasurer of the household “throwing about” medals during the act of homage.

Several types of medal were approved, with a general issue bearing the effigies of the King and Queen, and with different designs for senior civic officials, and for members of certain police, fire and ambulance services. The precedent of 1902 was followed for later coronations and resulted in the issue of medals that were designed to be worn to commemorate the ritual that was observed for three of Edward’s successors.

A few honours were established after the coronation. In 1907, for example, the King signed warrants that created the Indian Distinguished Service Medal for members of the Indian forces who had “distinguished themselves in peace or on active service” (Gazette issue 28034), and the Edward Medal for those who “endangered their own lives” in “saving or endeavouring to save the lives of others from perils in mines and quarries” (Gazette issue 28070). The Gazette also recorded the early use of other honours that emerged during Edward’s reign, such as the Polar Medal, decorations for officers of the naval reserves, and the King’s Police Medal.

Central Chancery

The task of managing the honours system evolved during the reign, and in April 1904 The Gazette reported that a central chancery was being created, and that “the issue of insignia and registration of warrants shall be carried out by the Lord Chamberlain’s Department, St James’s Palace” (Gazette issue 27663).

The Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood became responsible for preparing the warrants of appointment that carried the sovereign’s signature, as well as arranging for investitures, and delivering insignia to both home and overseas recipients. Separate provision continued to be made for a few orders after 1904, as the Victorian Order maintained its own chancery at Buckingham Palace until the 1930s, while the Order of St Michael and St George operated an independent chancery until the 1960s.

The Central Chancery was also involved in the corporate life of the orders that began to emerge during the Edwardian period. The more extensive ceremonial that was introduced at the start of the new century was not reflected in reports in The Gazette, as when the King attended the opening of the Chapel of the Order of St Michael and St George in St Paul’s Cathedral in June 1906, or the chapter to invest the King of Norway as a knight of the Garter at Windsor Castle in November of the same year.

The Central Chancery still operates from its base in London, and its name regularly appears in The Gazette in connection with the award of honours, as in the case of the New Year Honours list of 2023 (Gazette issue 63918).

Demise

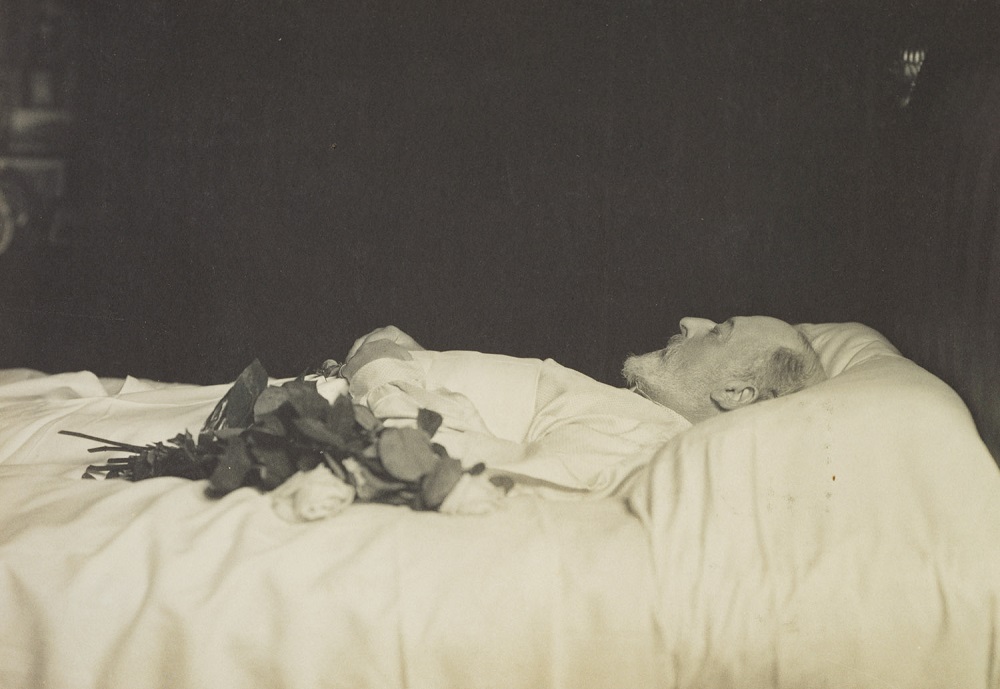

The Gazette announced that King Edward VII died at Buckingham Palace at 11.45pm on Friday, 6 May 1910, less than a fortnight after he returned from Biarritz (Gazette issue 28364).

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours.

Let us know what you think of this article by getting in touch. All feedback is welcome.

See also

Gazette Firsts: The history of The Gazette and royal coronations

The Demise of Queen Elizabeth II and Accession of King Charles III

Queen Elizabeth II - In Memoriam

Images (in order of appearance)

The Gazette

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2022

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2022

Getty Images

Russell Malloch

Helensq

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2022

References

- Sir Almeric Fitzroy, Memoirs Volume I (1928), page 288.

Publication date: 3 January 2023

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.