100 years of Women's Pioneer Housing

Women’s Pioneer Housing (WPH) is London’s largest specialist housing association for women and aims to make a positive difference to women’s lives. To celebrate WPH’s centenary year, we look at the history of the association and its origins after World War 1.

‘To cater to the housing requirements of professional and other women of moderate means who require distinctive individual homes at moderate rents’

Why was Women’s Pioneer Housing founded?

In post-1918 Britain there were over 1.75 million ‘surplus’ women. Many were unmarried and needed to support themselves on modest incomes; some had worked as nurses, clerks or typists during the war; while others had taken advantage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 and were joining the professional ranks for the first time in fields previously barred to women, like law and accountancy. The rapidly expanding community of single women workers meant an urgent need for adequate housing, which was particularly sparse in London.

In the aftermath of the World War 1, Prime Minister Lloyd George pledged to build ‘homes fit for heroes.’ The 1919 Housing Act, known as the ‘Addison Act’ after its sponsor, marked the beginnings of social housing. But the initial economic boom of the immediate post-war years was short-lived. By 1921 reconstruction plans were in difficulty and in the ongoing crisis the dire shortage of housing for women went unnoticed.

The options for female workers were limited to the likes of boarding houses and hostels. Landladies preferred male boarders as they were more likely than women to pay for extra services, such as the provision of meals and laundry services. Meanwhile hostels often had impressive facilities but residents had to adhere to curfews and cope with a lack of privacy in cubicle-style rooms.

How did Women’s Pioneer Housing begin?

How did Women’s Pioneer Housing begin?

In 1918 some women had been given the vote but the campaign for equal rights and opportunities continued. Housing was an important issue for women who wanted to live and work independently. Which is why in 1920 the Anglo-Irish suffragist, Etheldred Browning and a group of like-minded women founded Women’s Pioneer Housing.

Etheldred Browning was a campaigner on women’s work and housing issues. She moved from Dublin to London sometime after the war and worked for a short period with the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association (GCTPA). She was one of the housing campaigners at the time who recognised that the large number of Victorian villas, built for well-off families and with the expectation of an endless supply of cheap, mostly female labour, were proving hard to sell as fewer women wanted to go into domestic service and many people were looking for smaller homes. These houses were available for relatively small sums and could be converted into small flats. Etheldred wanted to take advantage of this opportunity and so she gathered a group of like-minded women around her, some of whom were experienced suffrage campaigners while some were supporters of the GCTPA.

The first meeting was held on 30 August 1920. Four women attended: Etheldred herself; her friend from Dublin, Florence Lily Carre; Miriam Homersham, who later became WPH auditor; and amateur architect Annabel Dott. The journalist and suffrage campaigner, Helen Archdale was one of four women who sent their apologies, however she played a vital role serving on WPH’s Committee of Management from 1920 until 1927, latterly in the chair. Etheldred was appointed Secretary and remained the sole member of staff until 1928. Women’s Pioneer Housing was registered as a Public Utility Society on 4 October 1920.

How was Women’s Pioneer Housing financed and run?

Initially, WPH relied on raising small amounts of funding from a distinguished network of mostly wealthy or well-connected women and a handful of men. The society hoped to take advantage of newly available government subsidies, but they did not materialise and WPH was faced with legal action regarding the purchase of its first property, 67 Holland Park Avenue. Ray Strachey, who chaired WPH’s Committee of Management from 1921 to 1922, came to the rescue, finding an anonymous donor. She also recruited a sympathetic lawyer and persuaded people with housing and planning experience to come on board.

Fund raising soon became more focussed. Contacts, friends and relatives purchased shares and loan stock, while wealthy women put up thousands of pounds in mortgages against new properties. In the early 1920s, borrowing from week to week, the Committee took financial risks to obtain new properties. By the mid-1920s the security in the houses and leases owned already was enough to allow further purchases.

By 1936 Women’s Pioneer Housing had 522 flats in 55 properties. By the time Winifred Martin took over from Etheldred Browning in 1938 there were 60 properties providing 574 flats. However, further expansion was temporarily halted by the outbreak of the World War 2.

What were Women’s Pioneer homes like?

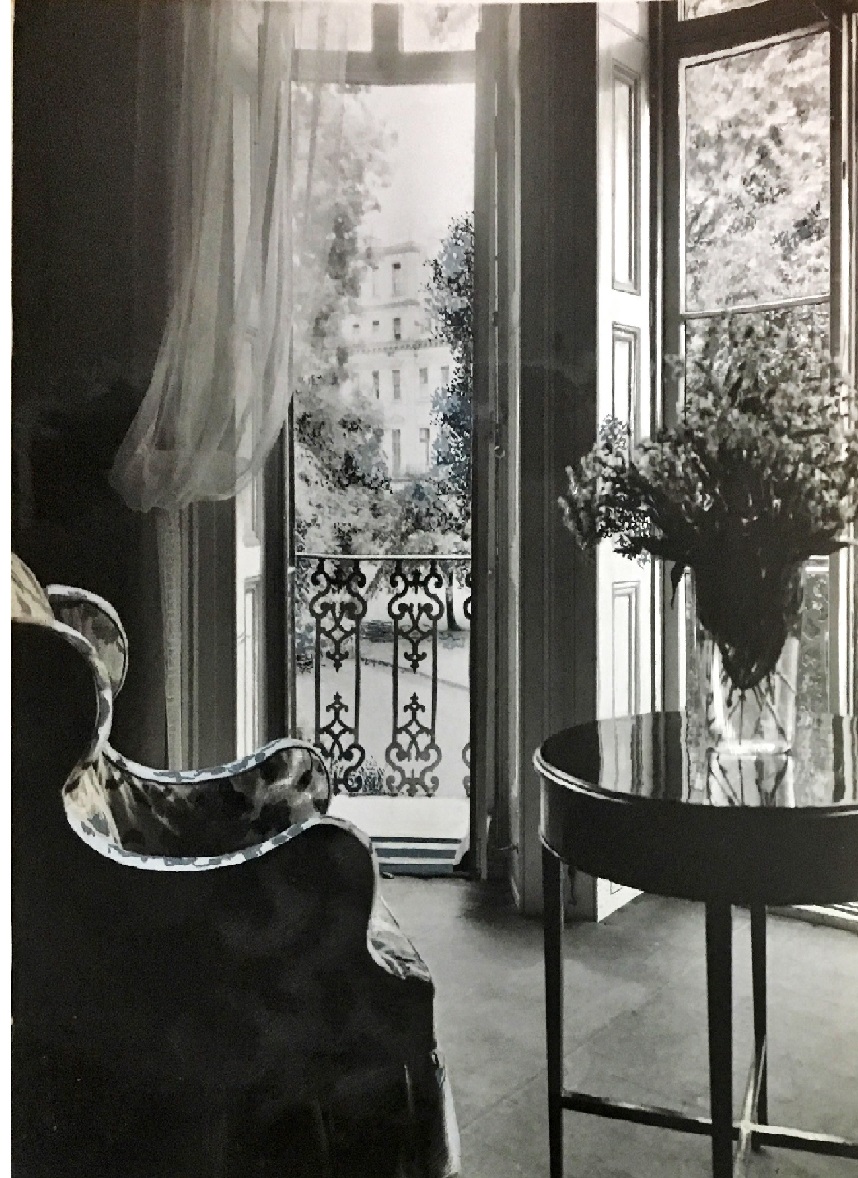

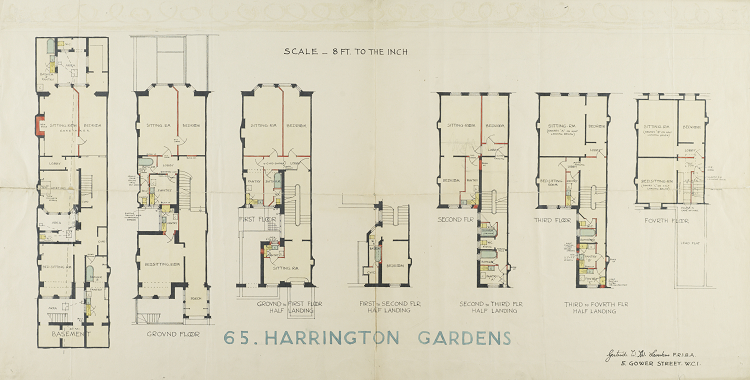

The first property, 67 Holland Park Avenue, was purchased in May 1921 and converted into six self-contained flats designed by architectural firm Hennell & James. In 1923 the Committee of Management commissioned Gertrude Leverkus, one of the earliest certified women architects. During the 1920s and 1930s, she designed and oversaw the conversion of around 40 Women’s Pioneer properties. Most were in North Kensington or Earl’s Court but there was a house with a garden in Putney and a property in Brighton that tenants could use for holidays.

In 1935 the society took over Browning House and Nightingale House in Hammersmith and Brook House in Acton. These had been purpose-built as flats after the war and were close to local hospitals and railway stations.

Who lived in Women’s Pioneer homes?

Women chose to live in Women’s Pioneer homes for many and varied reasons. Often friends or work colleagues recommended WPH homes to women moving to London for work. Some who needed homes were widowed or divorced, while some had to leave the family home when their last remaining parent died. Those who supported the suffrage cause were no doubt pleased to find housing designed and run by women, for women. Many girls leaving home and hoping to live independently also found women-only housing was acceptable to their reluctant parents.

Most of the women identified as WPH tenants in the 1920s and 1930s had paid employment. Analysis of 885 working age tenants shows that 81 per cent of them were undertaking paid work. The proportion of women who described themselves as ’living on private means’ or doing ‘unpaid domestic duties’ stayed at around 20 per cent for most of the interwar years but reduced sharply to 12 per cent for tenants who moved in during 1938 or 1939.

The overwhelming majority of tenants (91 per cent of 890 tenants) were born in the British Isles. Of the 77 per cent born in England, 43 per cent were born in London. Almost all of those born in the then British Empire had parents with strong links to Britain.

In WPH’s early years, 44 per cent of the tenants came from the upper middle-class, reflecting the requirement that early tenants invest in the society. This had dropped to 28 per cent by the 1930s. Around half of all tenants in the interwar years had lower middle-class origins, while the proportion of working-class tenants peaked at 22 per cent in the period 1933-1937.

What jobs and careers did the tenants have?

Ray Strachey’s book Careers and Openings for Women, published in 1935, documents a strong decline in domestic service, a slight decline in teaching and an increase in clerical work. Tenants from more modest backgrounds often worked locally as clerks.

One of the tenants at Nightingale House, Cora Nurse, was born in Fulham where her father was a coachman. She worked at the Post Office Savings Bank where jobs were allocated by open competition, providing opportunities for women from modest backgrounds. In January 1922, the London Gazette recorded her success in the Writing Assistant open competition (Gazette issue 32569).

Many residents were teachers, some were lecturers, and one, Constance Geary, left her WPH accommodation to become Principal of a Women’s University in Lahore. Edith Mary Flux and Alice Parker, both teachers, were tenants of WPH for 25 years at three different properties. After Alice’s death, Edith lived for a further 25 years. Mary Flux Court is named after her.

A few early residents were retired governesses or nannies, and some had formerly been employed as lady’s maids, cooks or housekeepers. Nursing was a long-established career for women and two WPH tenants, Marguerite Medforth CBE (Gazette issue 14762) and Anne Beadsmore Smith DBE (Gazette issue 33053), ended their careers as Matron-in-Chief of the Army Nursing Service. Orphaned when a child, tenant Ann Eliza Haydock also overcame a difficult early life to qualify as a nurse.

Also represented were masseuses and medical gymnasts, forerunners of today’s physiotherapists.

Several WPH tenants were pioneers in their fields. Ivy Davison, a tenant at Barkston

Gardens for almost thirty years, was a journalist for the Saturday Review and later Executive Editor at Geographical Magazine. Several tenants were distinguished scientists too. Dorothea Bate, for example, was

a self-taught palaeontologist and became the first female employee at the Natural

History Museum (NHM) and a world expert on the identification of animal bones. Dr

Helen Muir-Wood OBE (Gazette issue 41909) was also a geologist at the NHM and became the first woman Deputy Keeper. She studied

at Bedford College, University of London, under Dr Catherine Raisin, head of the Geology

Department, a WPH tenant when she retired. Dr Isabella Gordon OBE (Gazette issue 43010) was a marine biologist, the first woman to have a permanent job at the NHM and later

Principal Scientific Officer. Celebrated for her sense of humour, she wrote limericks

about crustaceans.

Also represented were masseuses and medical gymnasts, forerunners of today’s physiotherapists.

Several WPH tenants were pioneers in their fields. Ivy Davison, a tenant at Barkston

Gardens for almost thirty years, was a journalist for the Saturday Review and later Executive Editor at Geographical Magazine. Several tenants were distinguished scientists too. Dorothea Bate, for example, was

a self-taught palaeontologist and became the first female employee at the Natural

History Museum (NHM) and a world expert on the identification of animal bones. Dr

Helen Muir-Wood OBE (Gazette issue 41909) was also a geologist at the NHM and became the first woman Deputy Keeper. She studied

at Bedford College, University of London, under Dr Catherine Raisin, head of the Geology

Department, a WPH tenant when she retired. Dr Isabella Gordon OBE (Gazette issue 43010) was a marine biologist, the first woman to have a permanent job at the NHM and later

Principal Scientific Officer. Celebrated for her sense of humour, she wrote limericks

about crustaceans.

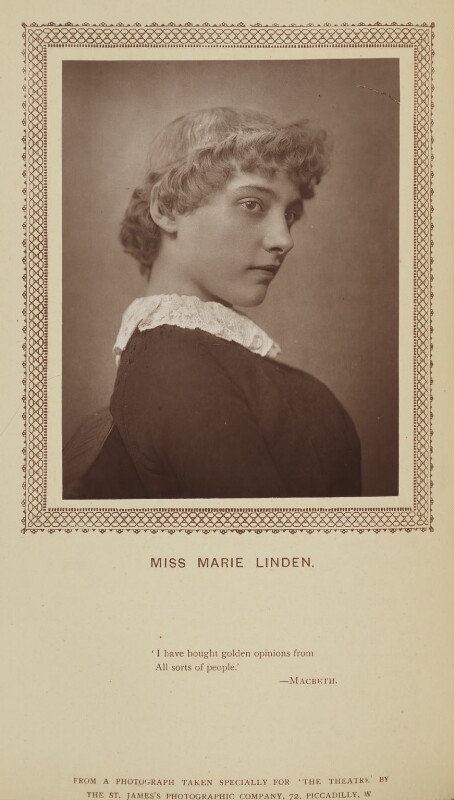

Some residents worked in the arts or were professional musicians. Marie Linden was an actress and tenant for 14 years and Katherine or Katrina Goodall (stage name was Katrina Tamarova) was a ballerina and appeared on television in its experimental days. Tenant Dorothy Mullock was an artist and costume designer who designed a poster promoting trips to the countryside by underground, while Jessica Lloyd Walters was a portrait, figure and landscape artist who joined the Suffrage Atelier (formed in 1909) where she learned printing techniques and produced several very striking posters and postcards for the suffrage cause. Jessica lived with her sister Ida in a WPH home from 1924 to 1929.

Business and self-employed women amongst the tenants included Cecilia Sanderson, a partner in a garage; Martha Pinkerton, a laundry proprietress; Ada Nettleford, a retired ‘own account’ corsetiere and outfitter; and Vera and Wilhelmina Blood, painters and decorators, who were employed by WPH in 1925 to undertake some decoration in the house where they had a flat themselves. Tenants Violet Jarrett and Mary Wilson ran a millinery business with many employees and premises with a large workroom and a showroom.

Women’s Pioneer Housing today

Women’s fight for the vote was simply the first step in a wider campaign for women’s rights in the early twentieth century. The centenary heritage project research underlines how having homes of their own enabled women to be independent to pursue careers and to live on their own terms. The last sixty years have seen huge changes in society and the housing services provided by WPH have adjusted to suit.

In 2020, WPH continues to provide homes and services that offer a springboard to independent women to achieve their potential. WPH aims to influence others to do the same; the importance of housing in tackling inequality for women is as relevant today as it was in 1920.

About the author

Sue Kirby is Heritage Project Lead and Women’s History Researcher. This article is based on original research by the Women’s Pioneer Housing volunteer researchers, Bonnie Emmett, Ann Sainsbury, Anne Sharpley and Jennifer Taylor and has been funded with the aid of a grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

See also

What is the 'Order of Wear' for British honours, decorations and medals?

This month in history: The Crimean War and the 1856 Treaty of Paris

This month in history: Sir Robert Walpole becomes Britain's first prime minister

Find out more

Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 (Legislation)

Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1919 (Legislation)

Publication date: 6 May 2020

Images (in order):

- Women’s Pioneer Housing

- 'Women’s Pioneer flat.' WPH archive, London Metropolitan Archives

- 'Plan for conversion of 65 Harrington Gardens, Kensington c 1931. WPH’s architect, Gertrude Leverkus, lived here in what had been the ballroom for thirty years.' WPH archive, London Metropolitan Archives

- 'Dame Anne Beadsmore Smith.' © National Portrait Gallery (ref 124811)

- Marie Linden, actress and WPH tenant. © National Portrait Gallery (9275)